Beer & Chocolate Language

When I first came to craft chocolate from the craft beer world, one thing was immediately clear: chocolate people didn’t talk about chocolate the same way beer people talked about beer.

Beer descriptions—on labels, in reviews, or elsewhere—tend to focus on a short and tangible list of tasting notes with very little romance added in. This contrasts with craft chocolate, where reviewers and even the makers themselves often focus on what you might be feeling as you taste their bars, rather than on exactly what you should be tasting. The inference is that while beer is intoxicating, chocolate is the drug that can alter your mind and tap into your deeper emotions.

The chocolate world is drenched in this kind of language, pulling in unlikely analogies, summoning emotion and memory and imagination, and unapologetically playing on whimsy and romance. Can and should craft beer grow in its willingness to move beyond purely concrete description to employ this kind of language? Can this language go too far and become distracting, losing sight of helping consumers in a haze of head-in-the-clouds whimsy?

Way back in the second episode of Bean to Barstool in 2020, I asked several experts from beer and chocolate why the chocolate world is seemingly more willing than the beer world to use evocative or fanciful language in description.

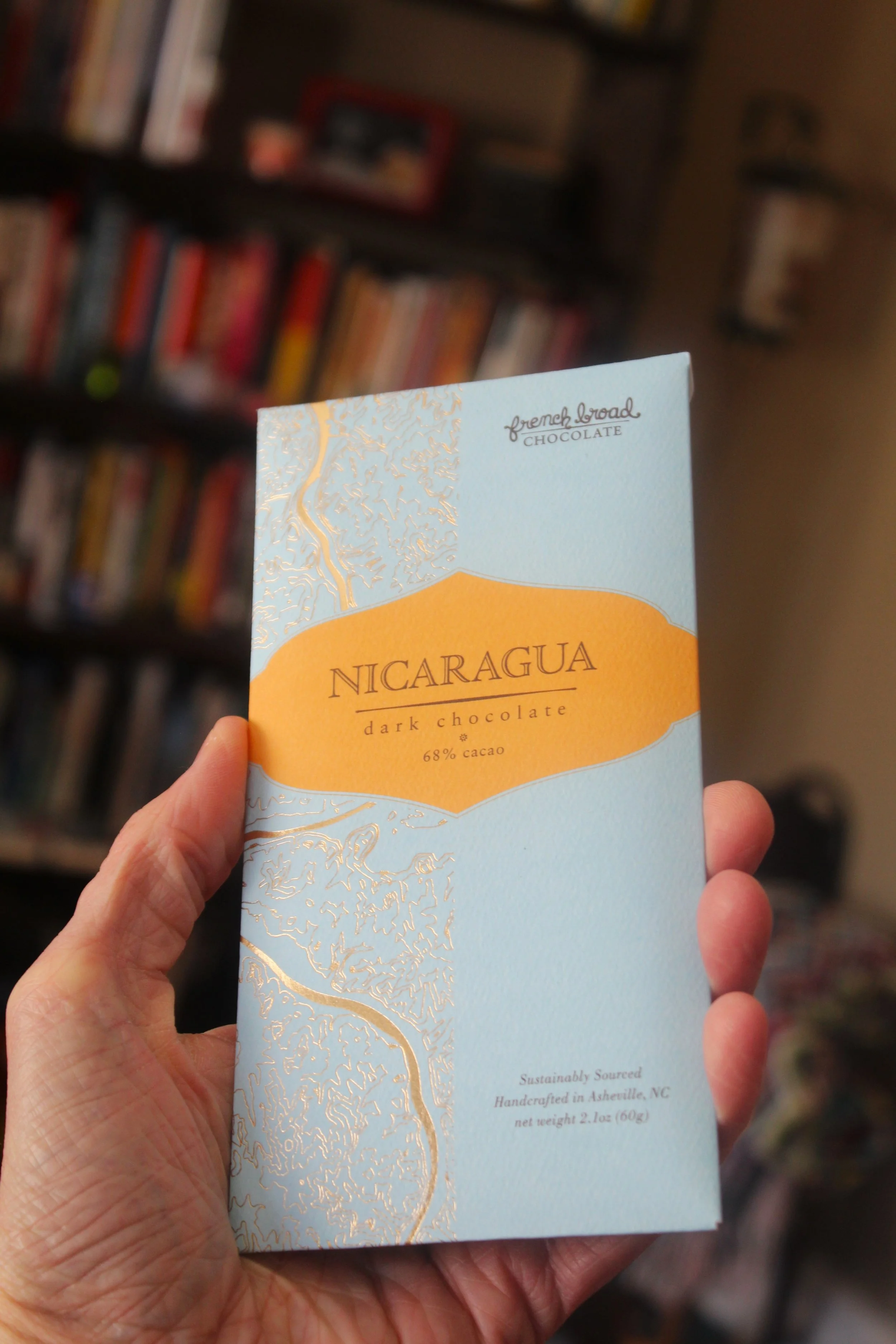

Through her own love of beer and French Broad’s extensive collaborations with craft breweries, Jael Skeffington, co-founder of French Broad Chocolates in Asheville, North Carolina, has had the opportunity to observe the distinction between how we talk about beer and chocolate. She observes that we inherently approach chocolate in a more emotional way than we do beer.

“I think it is just an association that we have with chocolate, that it’s emotional,” she says. “We use chocolate as a tool to manage our emotions, whether it’s used romantically, or to show care in friendship, or to comfort people when they’re feeling sad.”

She goes on to explain there might be some science behind this—some of the chemical compounds in chocolate can mimic the feelings of falling in love, and this becomes a feedback loop when we continue to associate chocolate with love, friendship, and comfort.

For chocolate writer Megan Giller, our willingness to be fanciful in talking about chocolate goes back to childhood.

“I really think it’s because chocolate is so nostalgic,” she says. “We have these very early memories of chocolate, even if it wasn’t a super fancy single origin dark chocolate. I think when you try a certain bar, it sometimes can evoke those memories, even though it has a different taste. It still taps into that very visceral memory.”

Most of us had our first taste of chocolate as children, and it was likely associated with special moments. Even as adults, we may still use chocolate as a reward for ourselves, an indulgence, and thereby perpetuate that childhood association. Our first memory of beer came only much later (hopefully, lol). For most people, beer and chocolate tap into different emotional and mental pathways when we taste them, and that affects the way we employ language around them.

“Because chocolate is naturally considered a childhood treat at the beginning of their introduction to pleasure, there is this built-in playfulness,” says chocolate educator London Coe, who runs Peace on Fifth in Dayton, Ohio. “There is a lot of expectation that you don’t take yourself too seriously. You can approach it in a childlike way.”

This permission to employ romance and whimsy in describing chocolate might be partially papering over a central problem in sensory description—our brains and chemical senses of taste and smell aren’t really set up for putting language to flavor. It’s one thing to share a childhood memory when you taste an excellent chocolate; it’s quite another to accurately describe the actual flavors that are bringing that memory to mind.

“Everybody who starts this process feels like they’re inept,” says Randy Mosher, a veteran beer writer whose comprehensive book on the human sensory system is forthcoming. “The process of creating language out of smell… Our brains are not very well suited for that. It’s amazing we can do it at all.”

The Need To Be Right

The American craft beer movement really got moving after homebrewing was legalized in 1979. Homebrewing allowed hobbyists to develop their skills before going pro and opening their own breweries. Homebrewing competitions were (and still are) the major events of the homebrewing world, providing expert feedback to help brewers improve their processes and recipes. The need to standardize the judging process for these competitions led to the birth of modern beer style guidelines, such as those published by the Beer Judge Certification Program and the Brewers Association. These guidelines provided concrete descriptive language for analyzing competition samples, and a generation of brewers, judges, and beer writers—the folks most responsible for our modern beer flavor vocabulary—were trained on this system. Consequently, beer has a pretty expansive and detailed (if still far too Eurocentric) flavor lexicon.

But this process didn’t leave much room for engaging emotion and imagination in describing beer.

“Style-based judging does have a bit of a deficit philosophically in that in minimizes wonderfulness,” says Randy.

It may also have the more insidious consequence of tying beer tasting to competitiveness and grandstanding, something the male-dominated world of craft beer has needed no help with.

Anyone who has spent much time in beer tasting circles knows the fear of “getting it wrong”—misidentifying an ingredient, missing an off-flavor, not using the scene-approved nomenclature for a particular flavor. I can only imagine how much more fraught this experience is for folks who aren’t straight, white, cisgendered men. In the last few years strides have been made toward eliminating some of this gatekeeping weaponization of tasting language, but it’s still present.

“In chocolate, you don’t have to be right,” says London. “The process of making beer is centuries old and has stayed very much the same in terms of technique. Chocolate is a little more adventurous, and for that reason is can be whimsical.”

Balancing Accuracy and Whimsy

While I think beer could benefit from making room for a little more romance, whimsy, and even humor in its descriptive language, none of us want to turn beer into wine, where runaway imagery can build opaque walls keeping consumers from understanding what a wine they’re considering will actually taste like. This type of description fails at its fundamental purpose: to help consumers make decisions.

“I think a little more romance in beer descriptions wouldn’t be a bad thing,” says Randy. “But there’s this quality [in wine] called bullshit, meaning that the descriptions that are written by a lot of reviewers bear no resemblance whatsoever to the wine that’s being written about. It’s very image-y, but it’s completely disconnected from the physical reality of the liquid.”

By returning to that childlike sense of wonder and discovery, even when we’re tasting an adult beverage, perhaps we could explore a more holistic vocabulary for describing beer flavors. However, it’s important though that we don’t lose the thing the beer world is actually quite good at—concrete flavor descriptions that help consumers make sense of the dizzying variety of beer styles on shelves today. Beer does a good job for the most part of helping consumers know some of what to expect when they open a bottle or can of beer. The problem is just that beer stops with those descriptions and often doesn’t seek to engage or appeal to the consumer’s imagination and emotions.

“[We need to do] a little bit of selling the story and helping people wrap their heads around the emotional experience,” says Randy. “Ultimately that’s why people buy beer, besides just the alcohol. They want it to make them feel something—feel happy, feel amazed, feel comforted, or whatever it happens to be. It’s complicated, but I think that’s the goal.”

If the goal is for a maker to give consumers both an accurate expectation of what a food or drink will taste like, as well as some deeper or more holistic reason to care about those flavors, what does that actually look like in practice? As Mark Dredge points out in this excellent blog post, it’s first going to depend on the intended audience and purpose. Assuming it’s for a consumer who has some personal interest in craft beer, the goal is to both provide that individual a description of what the beer will actually taste like, and then also tug them forward a bit with some more whimsical, esoteric elements.

It can help to think of flavor description on several different tiers.

The first tier involves technical analysis of flavors as related to the processes and ingredients used in production. This is an industry-focused description, one you might find during competition judging, and it might include pointing out specific chemical flavor compounds, the ingredients they’re derived from, and/or how processes or ingredients might be altered to eliminate, adjust, or amplify particular characteristics. A lot of this is unlikely to be useful or appealing to consumers, but a mention of some ingredients or a traditional or experimental process might be informative or intriguing.

The second tier is where craft beer typically excels: concrete flavor descriptors. This is a list of specific flavor, color, and texture notes one might experience in the beer. They might be directly from an actual flavor addition (maybe peaches were used so you’ll taste peach in the beer) or they might be evoked by other ingredients, such as notes of grapefruit and pine from Cascade hops or toasted bread crust from Munich malt. This will also include basic tastes you might find in the beer: sweet, sour, or bitter, most commonly. This tier lets the consumer know what the beer actually tastes and smells like.

The third tier will use some fanciful, image-rich language to evoke emotions or engage imagination, making the beer sound more appealing. This might mean saying that the Pale Ale that has those Cascade hops mentioned above is like having a citrusy picnic in the middle of a pine grove. There are endless options here for creating images or feelings in the consumer, and this doesn’t have to be far-fetched or masturbatory in the way the worst examples of wine language can be. Just go beyond the basics. Appeal to the mind and heart as much as the senses.

The final tier is descriptive copy that has no direct connection to the flavors contained in the beer, but is intended to put the taster in a particular mood or mindset. We can think of these descriptions as artist statements of a sort. They can range from philosophical voyages through the cosmos to poetic reflections on the natural landscape around the brewery. These can get away from us pretty quickly, but used sparingly can add a spark of mystery or excitement to a description.

Helpful but evocative beer descriptions might include a lot of tiers two and three, with elements of the others mixed in as appropriate. Some breweries go all in though.

I want to share an example from Burial Beer in Asheville, because they somehow manage to employ all of these tiers in almost every beer description. I could have picked any of their beers as an example, but here’s the description for The Lunar Pendulum of Vacant Light, a barrel-aged Barleywine. It starts out pretty obscure, but reels things in and ends up telling you everything you need to know.

These things appear within the confines of the unseen. From the cracks in our painted universe. From the belly of our bellowing consciousness. Into the swing of our imploding existence. A blend of highly beloved Barleywines, each having 10-18 months of Bourbon barrel aging lifetime. Aged upon a load of fresh banana, whole Madagascar Vanilla Bean, Spicewalla Cinnamon and a pleasing dose of Sea Salt. A violent pall of creme brulee, tableside bananas foster, and densely spiced banana bread.

They share ingredients and processes, specific flavor notes, fanciful flavor description, and mood-setting poetic statements, all in one succinct paragraph. Not every beer description needs all of those elements, but more than just a basic checklist of flavors would certainly be nice.

Craft beer is good at accurate flavor description, but it can get better at consistently using evocative, imaginative language by looking to the craft chocolate world, and chocolate can follow craft beer’s example by incorporating simple, accurate tasting notes along with its more poetic elements. The combination of accurate flavor description and fanciful language that appeals to the consumer’s imagination or memory or emotion will both improve consumer engagement, and also elevate the tasting experience. Within that, there’s freedom to just...have fun. To be whimsical, to play with language, to not need to be right every time.

When I started Bean to Barstool, I wrote that it was a dream journal written in the complex alphabet of beer and the eloquent vocabulary of chocolate. No, I don’t know exactly what that means either, but I do know I love talking about how we talk about flavor, and how language and flavor both interact with deeper aspects of who we are. And I think beer and chocolate can each learn from each other when it comes to describing those interactions.