Mission Chocolate’s Two Rivers Bar Tells a Story of Coming Together

By David Nilsen

In north central Brazil, in the state of Amazonas, two great rivers come together by the city of Manaus. The Rio Negro flows down from the jungles of northern Brazil from its headwaters in Colombia. For a time early in its journey it forms the border between Venezuela and Colombia, and where it turns south, the borders of both countries and Brazil converge in the center of the river. When it reaches Manaus after 1,400 miles, this massive river converges with an even larger waterway known as the Solimões upstream of this point. This confluence referred to as Encontro das Águas—Meeting of Waters—is the point at which the largest river in the world takes on the name Amazon.

Rivers join all over the world, but few do it as dramatically as the Amazon and her largest tributary. Due to differences in water temperature, current, and type and volume of dissolved sediments and minerals, the waters of the Negro and the Amazon refuse to blend. For 3.7 miles they flow side by side, the dark, tea-stained water of the Negro and the sandy, coffee-with-cream opacity carried by the Solimões touching but mixing, creating a striking contrast that has become a popular site-seeing phenomenon. Eventually, they put their differences aside and the Amazon sets about draining the largest river system in the world on its way to the Atlantic Ocean.

In São Paolo in southern Brazil, Arcelia Gallardo makes bean to bar chocolate at Mission Chocolate. She highlights Brazilian flavors in her bars, often using indigenous fruits and nuts, and these bars serve as an introduction for North American audiences to new ingredients. In perhaps her most iconic bar however, she lifts up Brazilian cacao itself, and in doing so pays tribute to the stunning Meeting of Waters.

Two Cacaos, Two Colors

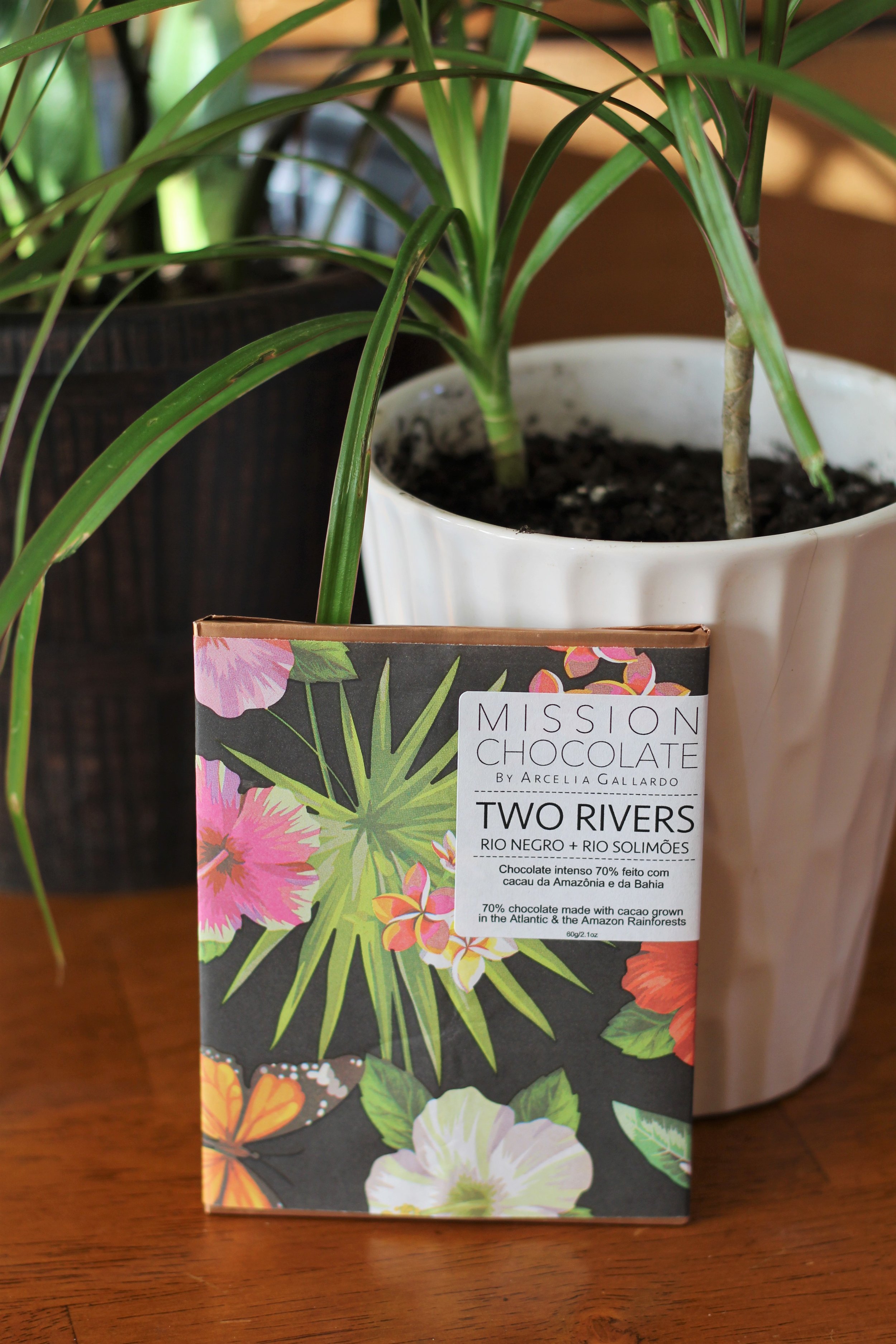

The two halves of Mission’s Two Rivers bar are markedly different shades of brown divided by an undulating center line. This 70% dark chocolate uses two Brazilian cacao origins—Amazônia and Bahia—and the contrast in colors and flavors nods to the stunning birth place of the Amazon. Fittingly, the chocolate maker herself years ago took a journey to acclimate into the current of a new culture.

Gallardo started out making chocolate confections in San Francisco before learning the bean to bar process at Dandelion Chocolate. She wanted to strike out on her own somewhere new, and rather than choosing Mexico, where she had family and spoke the language, she chose Brazil, where she knew no one and was an outsider.

“When I arrived to Brazil and was trying to understand Brazilian culture and geography, I took a trip to visit the Amazon,” she explains. “I went on a boat ride and they said, ‘We're going to now merge with this other river that's coming from another area of the Amazon, and you're going to see that it's just not going to merge. When I saw that, immediately I thought of chocolate. To me, it just looked like milk chocolate was coming from one side, and dark chocolate was coming from the other side.”

The visual contrast was poignant for Arcelia, who was not only acclimating to a new culture, but trying to put that culture’s nascent fine cacao industry on the map. For years Brazil had been known only for commodity cacao; no one made bean to bar chocolate from it. Arcelia and others makers worked with Brazilian farmers, and the cacao quality has grown considerably. Two Rivers celebrates that cacao and the beautiful landscape from which it grows, nourished by the waters of rivers that have taken their own meandering journeys.

“For me, the more I looked into this river, it really reminded me of Brazil as well, because at the end of the day, I am still a spectator in Brazil,” she reflects. “I'm still someone who’s here to learn to interpret my version of Brazil. For me, Brazil is people that come from Japan, from Africa, from Italy, Germany, from so many parts of the world."

A Confluence of Cultures

Two Rivers is a beautiful tribute to the confluence of cultures and to the currents that carried Arcelia from a familiar place to one where she had to adapt to a new language and culture and climate. It’s also a tribute to the work she and others in the Brazilian cacao and bean to bar chocolate industries have put in to improve the quality of Brazilian cacao and the opportunities available to its growers.

“It was a way for me to put two cacaos in one bar and not blend them, but prove that there is no such thing as one Brazilian cacao,” she says. “You have a cacao that's more acidic and produces a very creamy chocolate, a little bit nutty, and then you have another cacao that is fudgy and intense and it's bitter and dark. Two Rivers for me became one of my proudest bars because it taught people a lot. It taught people the geography of Brazil, it taught people a little bit of the story of Brazil, and it also taught people that there is no such thing as a basic Brazilian cacao.”

The largest river in the world has over 1,100 direct tributaries, eleven of which are over a thousand miles long each. They all have their own tributaries, which in turn have their own, down to the smallest streams tumbling down from the Andes or forming deep in the rainforest as mere trickles. Cultures are like this as well. The Amazon is many rivers, and countries are many cultures. Mission Two Rivers beautifully celebrates this.